Three Seconds of Pleasant Geometry

Back in the day, a compelling photograph could be taken in a fraction of a second and considered for years, even decades. The small world of street photography was dominated by photographers such as Henri Cartier-bresson, who said, “Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.” But today, while we may spend collectively a great deal of time taking shots, the time we take to consider their significance has been steadily whittled down, creating a vicious cycle of sorts not only in how photography is evaluated these days, but what kind of photography is made available for evaluation.

In the past, work that made it into the public consciousness came about due to the intent of a small, admittedly highly biased pool of individuals who had the opportunity and/or luck to gain access to a few select media.That state of affairs did change with the advent of the Internet, but rather than leveling the playing field as promised, it changed the channels through which this process could occur. Instead of a select few, mainly straight white men of means in Western countries who were able to forego other employment and afford the expensive equipment necessary at the time, the promise was that anyone with any camera could play, and after the wide adoption of mobile phone cameras, that future seemed to be in sight.

Except that hasn’t quite happened.To be sure, more people have access to photographic tools and the ability to make it widely viewable than ever before. The floodgates opened, but we still can only view so many images in a day. Someone, or something, had to assume the task of filtering the flood.

And someone did; you could say everyone did, in the form of pressing the “Like” or “Fav” button on their phones. But in order to translate those billions of touches into a semblance of hierarchy, something more was needed: Algorithms were employed to tell media outlets what kind of photos attracted the attention of the most people.

But the way we have been viewing these photos has resulted in a fundamental change in our tastes.

Viewing photographic prints has traditionally been seen as the best way to appreciate the full impact of a work. Then computers came into common usage, and though the first computer screens were woefully inadequate to the task, due to poor resolution, etc., they did geta great deal better. Looking at photos on a modern high-resolution, color-profiled screen became a joy, like a big, glowing print.As early as the mid-2000’s, when people mostly viewed images on large computer screens, sites like Flickr were the place to view photography.

Theoretically, this should have been the pinnacle of photographic viewing experience to this point: Large, highly detailed photographs with sumptuous colors and tones available at a touch of a button for our enjoyment. But even though it is possible to carry around a good-sized screen in the form of a tablet these days, that’s not what we’re doing.

Mobile phones have instead become the default media consumption tool; mobile sites like Instagram dominated the scene, trammeling website-based photography.As a result, most photos are viewed on small mobile phone screens in public settings. In this scenario, the details of a photo vanish into insignificance. You look down at your tiny phone screen in your hand, quickly sum up the general composition, the broad strokes of color, the heavy leading lines and general contrast, because that’s all you can see. It’s like squinting at a print hung on a wall from across the room. There’s no real way to get close; intimacy evaporates. Phone screen resolution has become exquisitely detailed in recent years, but the size is limited to one that can fit comfortably in one hand, and after having exceeded the human eye’s capabilities, resolution becomes meaningless. Likewise, strong, contrasting colors beckon from such screens far more than they do at larger sizes.

What we see is supposedly the general gestalt of an image, but what happens when something that aims to be more than the sum of its parts sacrifices those parts to emphasize the whole? Is it worth the time, effort and thought to make a photograph today that rewards the unlikely possibility of extended consideration beyond the mere facts of its geometry and colors, removing the end purpose of those factors in favor of their simple existence?

I can’t say which came first, the chicken of small-screen viewing or the egg of shorter attention spans. In any case, the audience of these tiny images is for the most part people with a bit of spare time, perhaps on our way to work or at lunch, spending a few seconds amid our other distractions glancing at photos on our phones, making a quick judgement before perhaps pressing the “Like” button, and then scrolling to the next one. If we’re deeply impressed (or, more likely, if we want to impress the photographer) we might type a series of exclamation marks, or perhaps even a real comment. I am confident by this point that, if a user with thousands or more followers follows me, it is done, possibly by a bot, in the hope that I will automatically follow them back. The bot will then unfollow me the next day.

This explains why the parts are sacrificed for the benefit of the whole; the “whole” here is not the photography, but rather getting people to pay attention to us.Consideration and appreciation have largely been jettisoned because not only do we not have the time, they, along with their goal, i.e. deciphering the meaning of a photograph, have both become extraneous to the more desirable process of gathering attention. This is not a coincidence, for although one depends on the other, once one is removed, the other will follow.

The inevitable dismantling of the old structures of photographic appreciation left space open to whatever primal impulses drive the public narrative of the day, even if the veneer of the old structures persists in an attempt to retain their aura of legitimacy.Many photography competitions these days feature social media prizes, and even the ones that don’t are inordinately influenced by such factors. Thousands upon thousands of photographers hustle to get their shots onto various popular online platforms, in anticipation of a deluge of likes, but no thought is given to time spent considering the images in question or the results of such theoretical evaluation. The shots we see are all pleasant to look at…strong leading lines, heavy contrast, enticing colors, perhaps a funny juxtaposition, and…not much else. They’re meant to impress, but only briefly. Once the button is clicked, their job is done.

This state of affairs is not Instagram’s doing, nor Facebook’s. In fact, not much has really changed in the grand scheme of things. As I’ve written in the past, photography has never truly been the mass media phenomenon its use in service of social media made it seem. We are not drowning in a “photographic flood” because “everyone is a photographer now.” It is true that everyone has a camera now. Everyone looks at photos on their phone. Everyone has a shorter attention span. Everyone likes attention. Exposure is our currency.

Is that not the norm, however? And isn’t meaning a subject for each viewer to decide themselves? Photographs, even at their best, have never themselves told stories…rather, they inspire us to conjure up our own realizations of their meaning. But what happens to our thought processes when the majority of the images jostling for our attention have done away with need for meaning beyond well-placed arrays of elements? Like lines of well-separated people in the frame, like funny shadows, like random hands, feet, or heads in isolation from their owners, like pleasing combinations of primary colors, like, scroll, like, scroll. How many of us even bother zooming in, if the app allows it, to take in the details of a shot, the expressions of the people, the relationships and connections within that reveal a deeper context? And does that even help us appreciate the details as part of the frame seen as a whole?

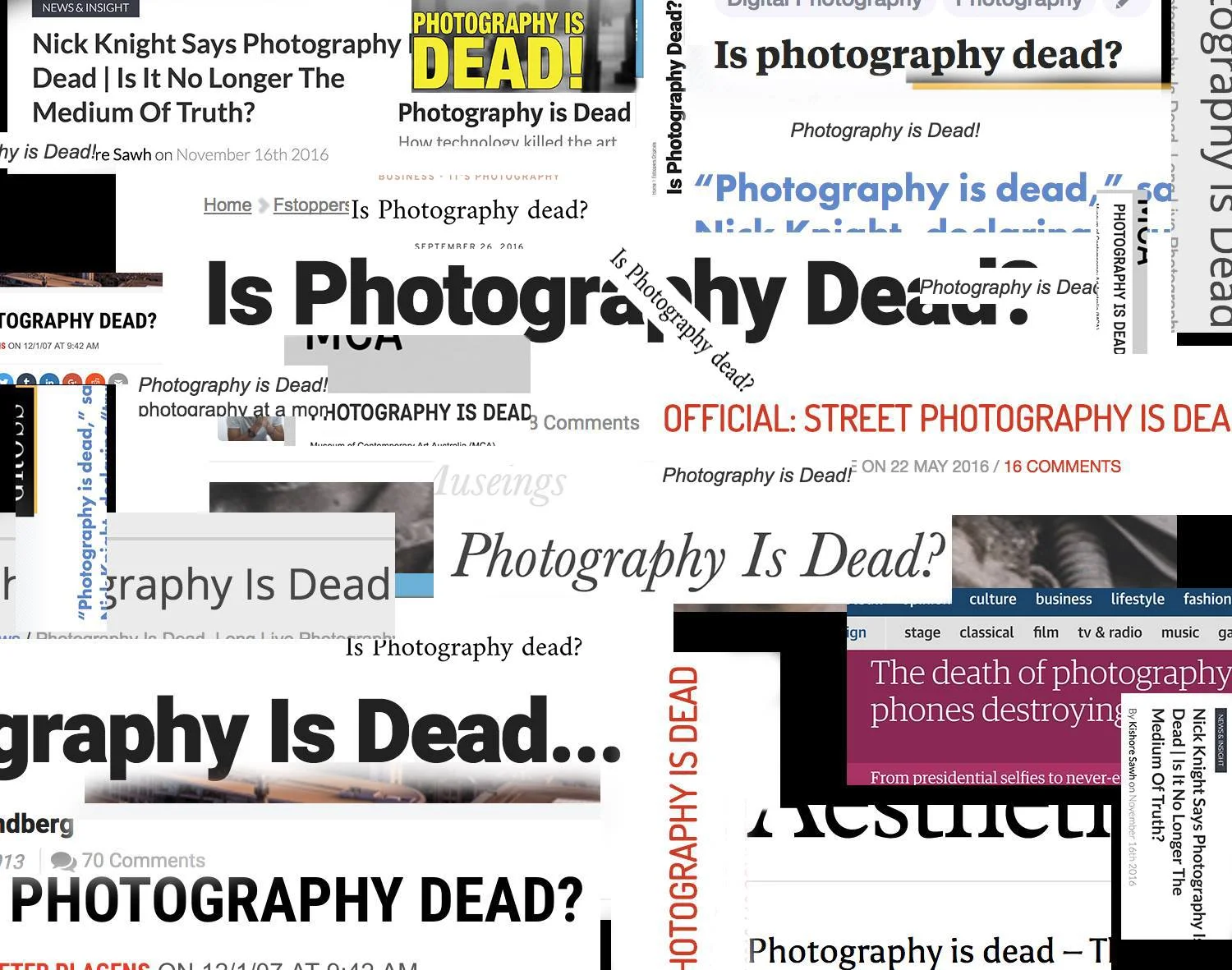

“Thinking too much” (AKA thinking) is looked down on more and more this era of snap judgement. Amid national and global emergencies real and imagined, cascades of memes rising and falling each second at speeds previously unimaginable,few have time for reasoned analysis, the benefits of which are falling by the wayside in the rush to dominate the lofty peaks of comments sections. Just as social media gave a false impression of vitality to photography, so has it also created a disingenuous impression of what “good” photography is, and the flying buttresses of this construction can be seen in the contests, promotions, Internet listicles, and features of the day.

Is it not possible, even preferable, for photographs to be arranged in a pleasant geometric fashion with lovely colors AND hold deeper levels of meaning? Absolutely, as long as the former is utilized in service of the latter.But are such compositions being noticed under the current state of affairs? And if not, where is the motivation for the majority of photographers to strive for such meaning in their work?

Cartier-Βresson once said, presciently, “The intensive use of photographs by mass media lays ever fresh responsibilities upon the photographer. We have to acknowledge the existence of a chasm between the economic needs of our consumer society and the requirements of those who bear witness to this epoch. This affects us all, particularly the younger generations of photographers. We must take greater care than ever not to allow ourselves to be separated from the real world and from humanity.”

Interesting work is still being done, if you look for it. It is often found in the modern equivalent of a closet shelf or desk drawer, languishing on the individual websites nobody visits any more, or perhaps in a smattering of zines nobody paid much attention to, or a project we didn’t bother with because the shots didn’t take advantage of the incredible color gamut of our iPhone screen. The good stuff is out there, as it always has been, languishing in the musty back stacks of libraries’ photobook sections or in our grandparents’ old shoeboxes. Occasionally, even now, some of it comes to light.

For about three seconds.

by TC Lin